Artifact Discovery Worksheet

Artifact Wish List

Hannah Prince Sampler

New Hampshire Marked French Musket

Maryland $2 Note

Stay Busk

Peter Keith’s Pocketbook

Spanish Pistol

Admiral Vernon Medallion

English Delftware Punch Bowl

Pockets

Chinese Tea Pot

Pipe Tomahawk Head

Payroll/Record

Curling Iron

Tea Caddy

1780 Counterfeit Massachusetts $20 Note

Cartridge Box

Spiked Tomahawk

Quadrant

Wagon-Jack

Tinned-Iron Brazier

Pattern 1742 "Brown Bess" Infantry Musket

Pair of Ice Creepers

Spontoon Bearing the Cypher of Landgrave Frederick II of Hesse-Cassel

French Model 1766 Cavalry Pistol

Spanish 8 Reales "Piece of Eight"

American Flintlock Fowler

Lantern

Miniature Portrait of Dr. James Craik Craik (1730-1814) by Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827)

-

Hannah Prince Sampler

Date: c. 1787

Origin: Marblehead, MA

Materials: Silk, Linen

Dimensions: 15⅞” L x 12⅝” W

Gift of the Ladies Auxiliary of the Texas SAR

Hannah Prince was born on March 19th, 1775 in Marblehead, Massachusetts one month before the battles of Lexington and Concord. Marblehead was a hub of activity during the Revolutionary War and multiple members of Hannah’s extended family served in the Revolution. Growing up in the midst of the American Revolution, Hannah learned how to sew and embroider. At age 12 in 1787, Hannah completed this sampler demonstrating her skill in needleworking and her educational accomplishments. This is a very early example of Marblehead samplers. Hannah was extremely talented and featured objects and imagery rarely seen in samplers from the area including animals, insects, and various flowers.

-

New Hampshire Marked French Musket

Date: 1771-1774

Origin: France

Materials: Wood, Metal, Lead, Brass

Dimensions: 57¼” Lx 1¾” W x 8” H; Bayonet: 18” L; Barrel:41⅞” L

Gift of Derek Brown, California Society

One of the most significant contributions France made to the Continental Army was weaponry. In early 1777, nearly 17,000 muskets were smuggled through the British blockade and delivered to New England. This musket likely arrived in Portsmouth, New Hampshire on April 20 or 21, 1777. It is one of the first of around 100,000 such muskets supplied by France. Marked with a “NH” stamp several times, this musket was issued to New Hampshire troops and remained in the state arsenal into the 19th century.

-

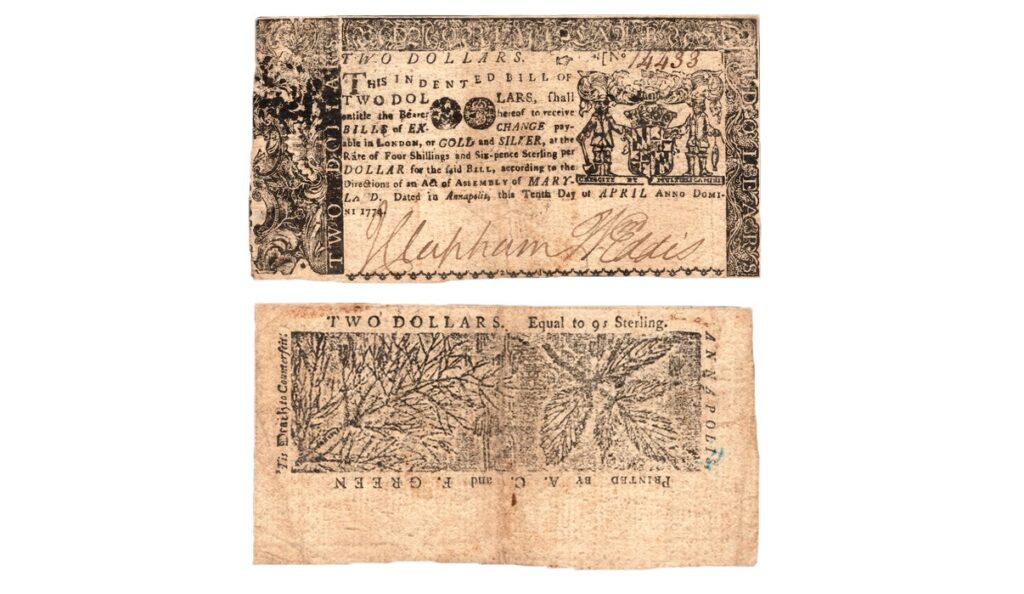

Maryland $2 Note

Date: Issued April 10th, 1774

Origin: Maryland

Materials: Paper

Dimensions: 4⅝” L x 2⅜” W

Gift of PG Davis Wright, Delaware Society; Paul Callanan, Michigan Society

Spouses and business partners Anne Catherine and Frederick Green printed this note. Following Frederick’s death, Anne Catherine carried on their printing business. Despite the domestic expectations placed on colonial women, Anne Catherine Green proved a successful and shrewd business owner. She is the only colonial woman credited with printing currency and one of the first to operate a newspaper.

-

Stay Busk

Date: c. 1770

Origin: Pennsylvania

Materials: Wood

Dimensions: 14¾” L x 2½” W x 1/8” D

Gift of the Missouri Society

Typically carved by 18th century men as a romantic gesture for a woman, busks served as personal gifts of love and affection. They were worn near a woman’s heart as a gesture of keeping a loved one close, and to further promote upright posture. Soldiers and sailors sometimes carved a busk as a token of their love before leaving for duty. This example was likely made in southeastern Pennsylvania and is dated “1770”.

-

Peter Keith’s Pocketbook

Date: c. 1765

Origin: Connecticut

Materials: Wool, Linen

Dimensions: 5¼” H x 7” W x ½” D

Purchase of the Museum Board

This pocketbook belonged to Peter Keith of Thompson, CT and is marked “PK 1765”. 18th century women made colorful pocketbooks decorated with “Irish Stitch” patterns for male loved ones. These pocketbooks held currency and documents. Keith served as a lieutenant in the Connecticut militia during the Battle of Saratoga in 1771 and may have carried this pocketbook during his service.

-

Spanish Pistol

Date: c. 1760

Origin: Spain

Materials: Wood, Steel, Brass

Dimensions: 19¼” L x 4” H x 2” W; Barrel: 11¾” L

Gift of James and Teri Lindley, Washington Society

The role and support of Spain during the American Revolution is often underrepresented. Reluctant to supply the rebellious colonies with as much aid as France, Spain covertly shipped valuable weapons, material, and money to the colonies even before the Revolution began. A Spanish merchant arranged to ship 1200 pistols to Massachusetts in early 1775, which likely included Pattern 1752 pistols like this one. Pistols such as these are commonly found in archaeological digs and were also likely used by Spanish troops under Bernardo de Galvez.

-

Admiral Vernon Medallion

Date: 1740-1749

Origin: England, Possibly North America

Materials: Bronze

Dimensions: 1.47" DIA

Gift of Patrick Neimann, North Carolina Society

Admiral Edward Vernon was one of Britain’s most well-known war heroes of the 1740s. This medal commemorates his capture of the Spanish city of Porto Bello (present day Panama) in 1739. Thousands of these medals were sold in Great Britain and the colonies. Lawrence Washington served in this campaign and named his home after the Admiral. Mount Vernon would pass to his younger brother, George Washington. This medal documents the growing influence of the British Empire, the ties and pride of American colonists, and the close ties between the Washington family and the British military.

-

English Delftware Punch Bowl

Date: 1775-1780

Origin: Westerwald, Germany

Materials: Clay, Lead

Dimensions: 3¾” H x 9¼” D

Gift of the Missouri Auxiliary

Prior to the Revolution, many colonists were patriotic British citizens and believed they were the most fortunate people alive. Punch bowls served as center pieces at parties in British culture. British Americans used punch bowls to toast the benefits of British citizenship, including “Trade and Navigation” which may allude to the Navigation Acts. These Acts structured the colonial economy and created a steady flow of products to the colonists. Resistance to trade controlled by the Navigation acts became a cause of the American Revolution.

-

Pockets

Date: 1760s

Origin: North America

Materials: Silk, Linen

Dimensions: 16” H x 12” W

Gift of Stephen & Jacqueline Miller; Priscilla “Cilla” G. Leed Tomme, SAR First Lady 2016-17; Lisa S. Gregory, California Ladies Auxiliary; Mary L. Addington, Tennessee Ladies Auxiliary

Pockets were not sewn into women’s garments, instead they were attached to ribbon and worn around the waist. They carried many items that were needed throughout the day. During the Revolutionary War, many women took over family businesses or traveled with troops providing vital services such as cooking, laundry, and selling general goods. A pair of pockets like these would have been vital to carry all that they needed.

-

Chinese Tea Pot

Date: 1760-1780

Origin: China

Materials: Clay, Lead

Dimensions: 6” H x 7½” W x 5” D

Gift of California Ladies Auxiliary

British Americans regularly drank tea with friends, family, and neighbors. Their choice of tea and tableware reflected the taste and status of the host. Highly popular tea leaves and sets were imported from China. Artisans made tea pots like this one to meet the tastes of American consumers. The Tea Act of 1773 gave the struggling East India Company a monopoly over imported Chinese tea to the colonies. American colonists viewed this monopoly as unfair and another attempt to tax colonists. Social gatherings became a place of protest as some colonists stopped drinking tea in response.

-

Pipe Tomahawk Head

Date: 1750-1800

Origin: Europe or North America

Material: Iron

Dimensions: 9L x 1W x 3H

Gift of Derek Brown, California Society

Native American protocol called for each participant of a diplomatic session to partake in a ritual pipe smoking. A pipe used for communal smoking of tobacco was an instrument of peace. Alternatively, a tomahawk used to fight was an instrument of war. Through one instrument, leaders could symbolically choose the pipe and peace or the tomahawk and war. Versions of the tomahawk or hatchet existed on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean as tools, but Native Americans pioneered methods of using it as a weapon. The result was a swift style of fighting that was effective against straight-line European tactics.

-

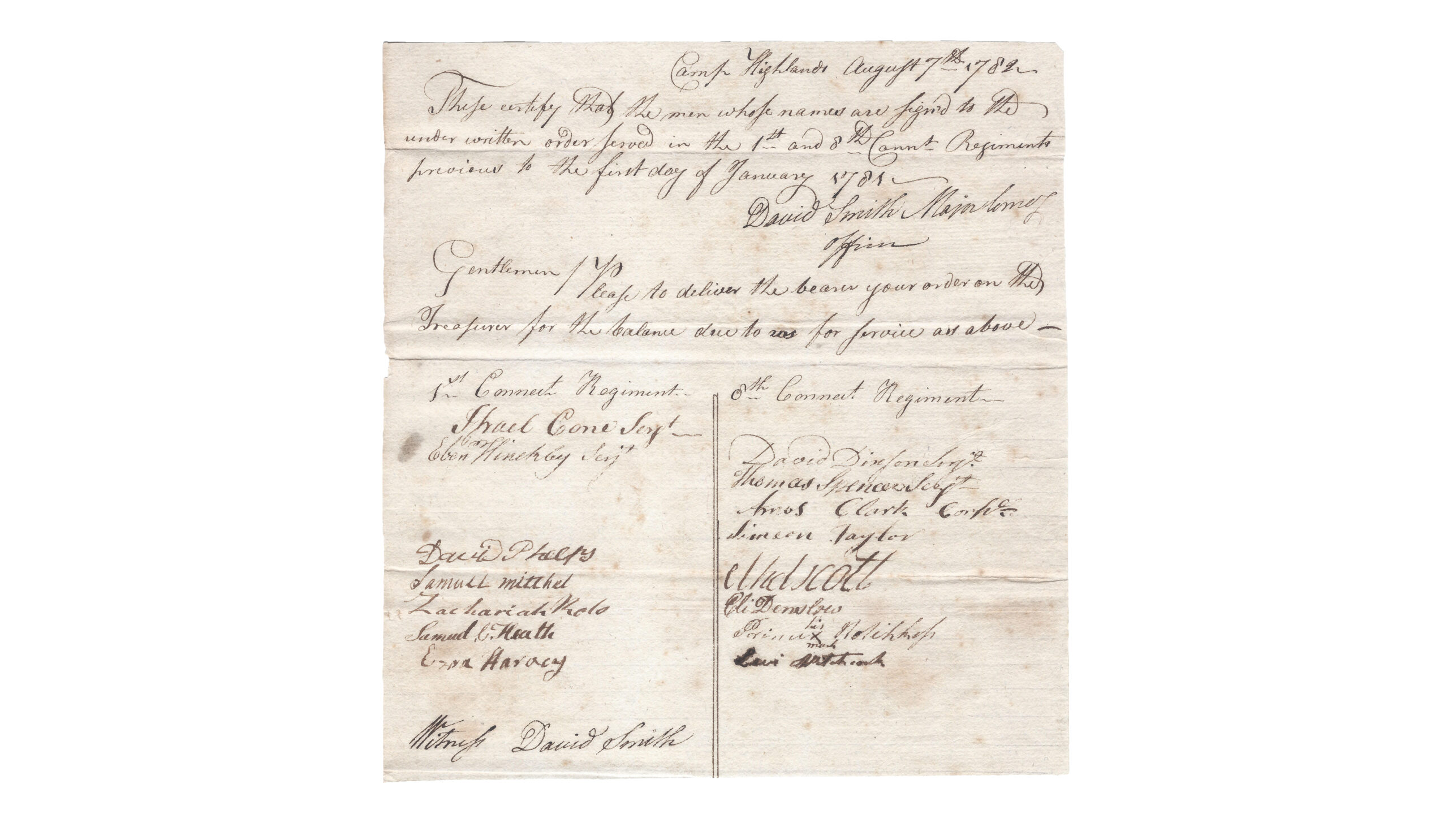

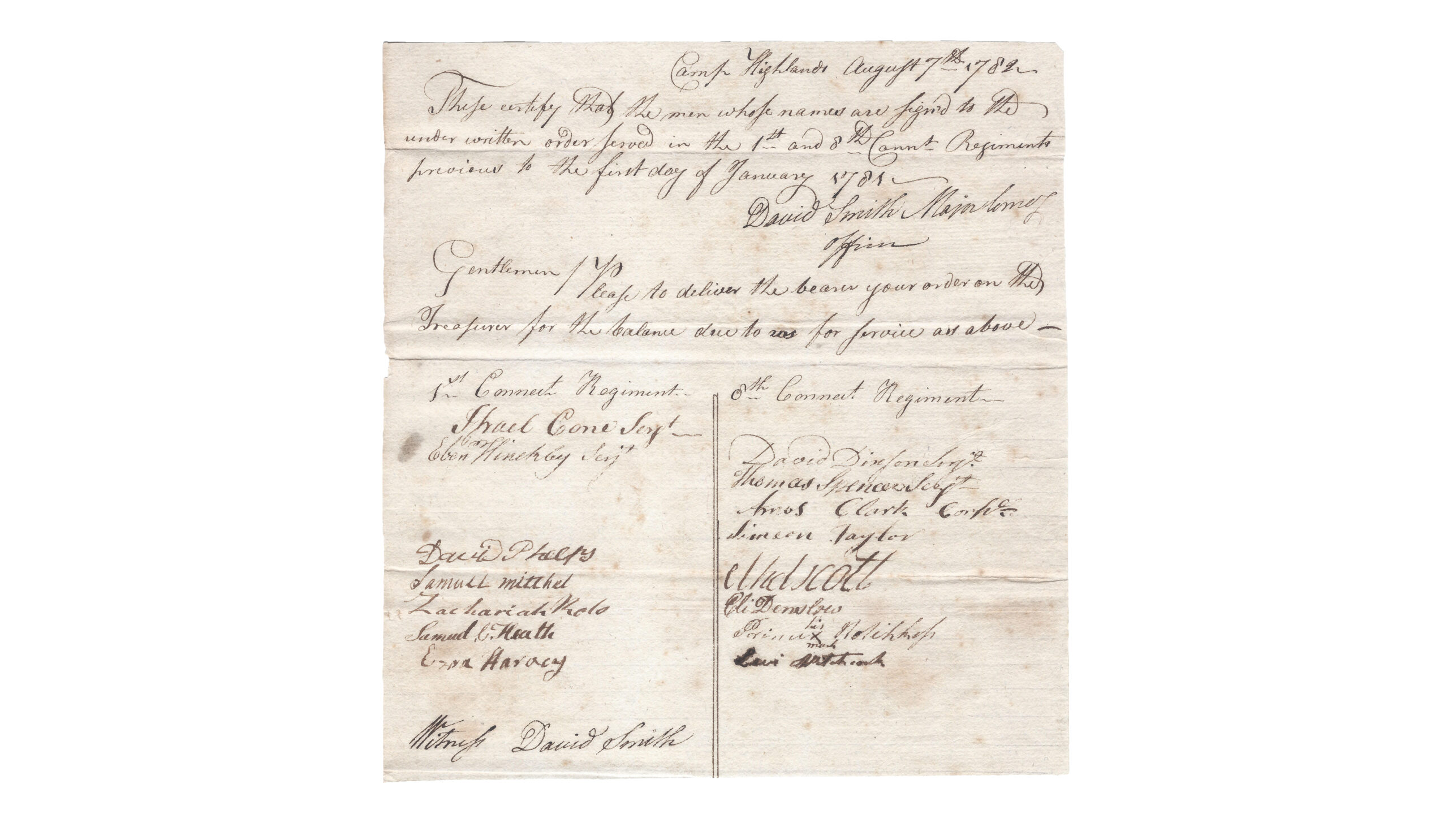

Payroll/Record

Date: August 7, 1782

Origin: North America

Material: Paper

Dimensions: 8 ½L x 8W

Gift of The Nay and Roberts Families of the California Society

Prince Hotchkiss enlisted in the 8th Connecticut Regiment on June 4, 1777, for the duration of the war making him one of the approximately 5,000 soldiers and sailors of African descent, both free and enslaved, who served the Revolutionary cause. His regiment saw action at the Battle of Germantown, Siege of Fort Mifflin, and Battle of Monmouth. It remains unclear if Hotchkiss was free or enslaved prior to the Revolutionary War, but his Black ethnicity is confirmed through descriptive muster rolls taken at Valley Forge. Here, Hotchkiss marked an “X” by his name to confirm backpay owed to him.

-

Curling Iron

Date: 1750-1840

Origin: Probably American

Material: Iron

Dimensions:9 5/16” Long x 2 9/16” Wide x ¼” Deep

Gift of James M. Perry, Maryland Society

Throughout the 18th century, colonists followed the latest fashions coming out of London. As a result, colonists wore a variety of wigs made from goat, horse, human, or yak hair. In the 18th century, wigs symbolized wealth and status. Curling irons such as these were instrumental in caring for wigs. Just like curling irons of today, but heated by fire instead of electricity, these irons shaped and curled. Wigs were taken to a wigmaker who also offered styling and barber services or were cared for by the wearer themselves, using tools such as this iron.

-

Tea Caddy

Date: 1770s – 1810s

Origin: Probably Great Britain

Materials: Wood, Leather, Tin, Felt

Dimensions:12 ½” Wide x 6 ¾” High x 6 ½” Deep

Gift of Ian Cunningham, Ohio Society

Care for a cup of tea? Tea Caddies were used to store and dispense tea at home. They were often made to follow the latest design trends and this tea caddy is in the Georgian style, popular from the late 1770s’s to the early 1800’s. This style often incorporated a simple design but with elegant details inside and out of the box. Tea caddies were a symbol of status and served as a centerpiece for gatherings. Often made from valuable mahogany with decorative designs, tea caddies typically feature a lock and key. Boxes such as these were locked to prevent theft from the waitstaff. This tea caddy may have been used before, during, or after the American Revolution.

-

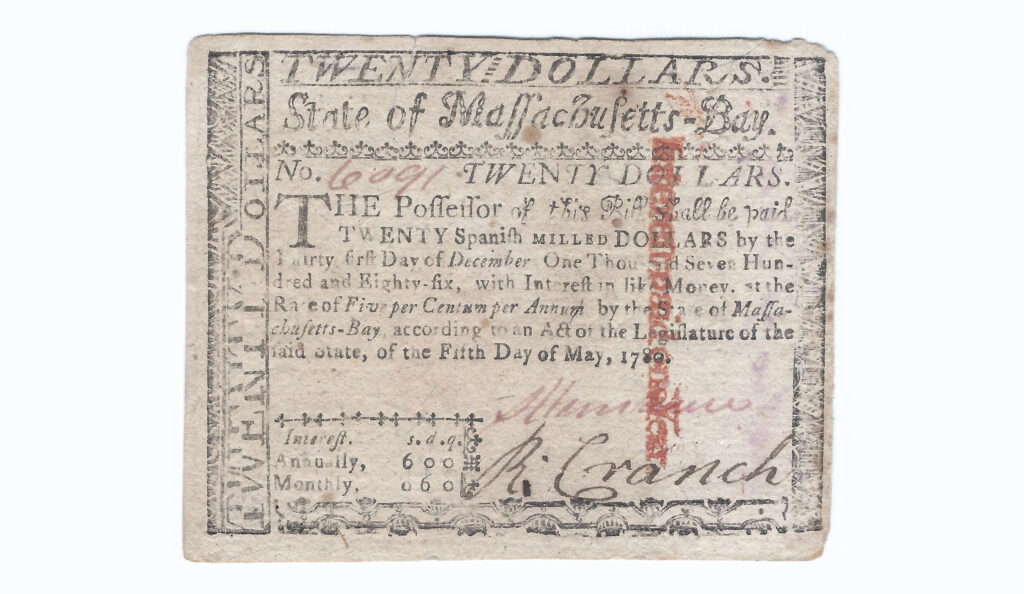

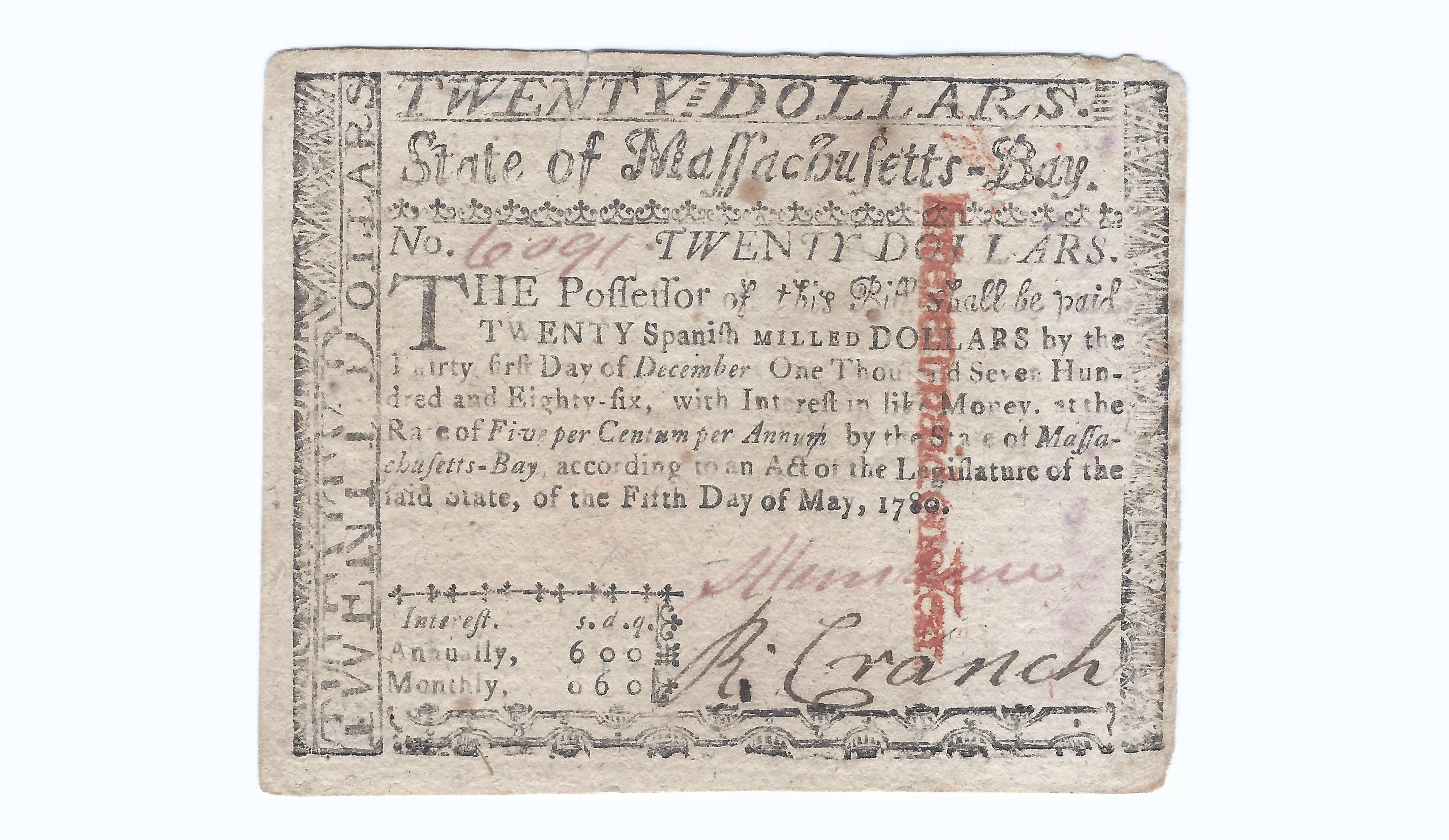

1780 Counterfeit Massachusetts $20 Note

Date: 1780-1786

Origin: North America or Great Britain

Material: Paper

Dimensions: 4 ¾” High x 3 5/8” Wide

Gift of Paul & Keitha Callahan, Michigan Society

Leading up to the American Revolution, colonial paper currency was often based on the Spanish 8 Reales or “Piece of Eight.” After the Revolution began, Congress and the states issued paper currency to help pay for the war effort. This paper money lost value quickly during the war due to many factors, one cause being counterfeiting. During the American Revolution, British and Loyalist printers produced fake currency such as this one which lowered the value of the real notes. By making the paper money worth less, Congress and the states had difficulty paying for supplies, material, and their own troops. This counterfeit is well done and requires close examination to tell it is not legitimate. Counterfeit notes like this serve as an example of early economic warfare.

-

Cartridge Box

Date: Circa 1775-1820

Origin: Probably American

Materials: Leather, Wood

Dimensions: 10” Wide x 4” High x 3” Deep

Gift of Robert Moore, Hawaii Society

This cartridge box would have been an important piece of equipment for a soldier on the battlefield. Cartridge boxes protected gunpowder and ammunition from the elements. A cartridge is a paper tube that contains everything needed to fire a musket including gunpowder, wadding, and a musket ball. This cartridge box has the capacity to hold 24 cartridges of .69 caliber musket balls. It has belt-loops so it could be worn on the hip where it was easily accessible for fast reloading. Boxes varied from simple designs of two pieces of leather sewn together with a drilled wooden box inside, such as this one, to some incorporating decorations and insignias of regiments or battalions.

-

Spiked Tomahawk

Date: 1750-1800

Origin: European, Native American, and possibly American

Materials: Iron, Wood

Dimensions: 11 3/8” High x 5 1/4” Long x 5/8” Wide

Gift of Dr. J. Fred Olive III, Alabama Society

Spiked tomahawks were a uniquely shaped weapon and tool that were probably introduced to North America by English traders. They were most popular around the years 1725 to 1800 across the region that consists of the modern-day states from New York to Maine and southeast Canada. Native Americans in this region are known to have favored spiked tomahawks and a Native individual may have used and decorated this one. Although Native Americans, Europeans, and colonists used tomahawks or hatchets as tools, it was Native Americans who adapted the tool to become a fierce weapon. The result was a style of fighting that was unique to North America in the 18th century. The tomahawk became an important ceremonial, cultural, and diplomatic symbol for Natives, Europeans, and Americans. The impact of this style of fighting developed by Native Americans can be seen throughout the era of the American Revolution.

-

Quadrant

Date: 1770-1775

Origin: Liverpool, England, Great Britain

Materials: Wood, Brass, Ivory, Glass

Dimensions: 17 1/2” High x 13 3/4” Wide x 3 1/2” Deep

Gift of the Sacramento Chapter SAR

Knowing a ship’s latitude is very important to keeping it on course to its destination. This measurement allowed sailors to know their location even when they had not seen land for days or even weeks. A quadrant helps a sailor measure the height of the sun from the horizon by measuring the angle. With this information, the sailor could then calculate the ship’s distance from the equator, or latitude. The name quadrant comes from the fact that this tool can measure up to 90 degrees, or 1/4 of a circle, leading to the use of “quad” which means “four”. Sailing the Atlantic Ocean in the 18th century was always a risk. The better a ship could stay on course and keep track of its location, the faster the voyage. A faster voyage meant less risk of running into bad weather, less risk of running out of supplies, and less risk of falling into enemy hands. Staying on course could mean victory or defeat at sea during the American Revolution. -

Wagon-Jack

Date: 1780s-1790s

Origin: Probably America

Materials: Wood, Iron

Dimensions: 24 3/8” High x 7 7/8” Wide x 9 1/4” Deep

Gift of N.S.C.A.R. in Celebration of their 125th Anniversary

An army on the march during the American Revolution could not carry all the supplies and equipment it needed. Hundreds of wagons full of food, cookware, and tents would follow behind the marching army. Along with those wagons there were also cannons on carriages that had to travel with the troops. A jack such as this one was a necessary piece of equipment to have in case a wheel, axel, or hub on a wagon or carriage broke and needed to be fixed or replaced. It functions much like jacks found in many mechanic’s shops today. -

Tinned-Iron Brazier

Date: 1750-1800

Origin: Probably American

Materials: Tinned-Iron, Wood

Dimensions: 16 1/4” Long x 10 1/8” Wide x 7 1/2" High

Gift of C. Bruce Pickette, Alabama Society

A brazier is a portable container used to burn wood or charcoal to produce heat. The heat of braziers was used to warm a room, heat wig curling irons, and cooking. The three flat surfaces around the rim of this brazier could serve as a pot or pan holders when it was used to cook. Braziers were made in many shapes and out of several materials at the time of the American Revolution. This tinned-iron brazier weighs less than those made of wrought or cast iron. Tinned iron is made by coating thin sheets of iron with a layer of tin to prevent rusting. The use of light weight tinned iron would have made this brazier perfect for a traveling army. -

Pattern 1742 "Brown Bess" Infantry Musket

Date: 1742-1800

Origin: Britain and America

Materials: Wood, Iron, Steel, and Brass

Dimensions: 61 7/8” Long x 8 1/2" High x 2 7/8” Wide

“Brown Bess” was the name British soldiers gave to the muskets they used during the 18th century to refer to it as their friend or companion. This one was likely sent to North America before or during the French and Indian War and may have been used by British soldiers or their American allies during that war. By the time of the American Revolution, this pattern of “Brown Bess” was outdated, and British troops carried newer ones. The Continental Army and militias did not have enough muskets to fight with, so they had to use older firearms left over from the French and Indian War like this one. Some of its parts were replaced with ones made during or after the American Revolution and the barrel was shortened. These changes point to this “Brown Bess” being used by American soldiers during the American Revolution and perhaps during the War of 1812. -

Pair of Ice Creepers

Date: 1750-1800

Origin: Probably Colonial American or American

Materials: Iron

Dimensions: 8” Long x 4” High x 4 1/2” Wide

Gift of Susan and Larry Crabtree, Alabama Society

Due to the lack of travelable roads in the colonies and early United States, rivers and streams offered the best options for travel. In those areas where temperatures got low enough for waterways to freeze enough for people and animals to walk on, residents and soldiers would wear ice creepers to traverse “frozen roads”. Accounts from Revolutionary War soldiers describe how they would wear ice creepers on the bottom of their shoes or boots in order to walk up or down a frozen waterway. They would often lead a horse or mule that was pulling a sled packed with supplies. A frozen river presented a great opportunity to transport supplies up or down the waterway to fortifications located along the riverbank. These forts then protected boat routes on the river during warmer weather. Ice creepers were also used in towns and villages when the ground was frozen, slushy, or snow covered. -

Spontoon Bearing the Cypher of Landgrave Frederick II of Hesse-Cassel

Date: 1760-1785

Origin: Europe

Materials: Iron

Dimensions: 75” Long x 5” Wide x 1 1/4” Deep

Gift of PG Joseph W. Dooley, Virginia Society; Bruce Buehler, Alabama Society; John Bredenfoerder, Ohio Society; Dr. Darryl Addington, Tennessee Society

The British Army did not have enough soldiers to send to North America in response to the American Revolution. King George III of Great Britain asked his German cousin Frederick II of Hesse-Cassel and other German leaders to lend soldiers to the British Army. Frederick II sent more than 20,000 soldiers to fight with the British. These German soldiers came to be known as “Hessians” and many Americans feared them. This spontoon bears the cypher “FL” for Frederick Landgrave on both sides and would have been carried by an officer to show their rank. Spontoons such as this one were more like a piece of the uniform but could serve as a weapon if need be. It is not clear if this spontoon was carried during the American Revolution, but it certainly could have been found in a “Hessian” officer’s hands. German soldiers were recognized for their excellence during the war. Many chose to stay in the United States and start a new life after the war rather than return to Germany. -

French Model 1766 Cavalry Pistol

Date: 1766-1770s

Origin: France

Materials: Wood, Iron, Steel, Brass

Dimensions: 15 3/4” Long x 6” H x 2 1/2” Wide; Barrel: 9” Long

Gift of PG Joseph W. Dooley, Virginia Society; Dr. M. Kent Gregory, California Society; and James Klingler, California Society

Beginning in 1777, France began secretly sending military supplies to the Continental Army. The French saw an opportunity in the American Revolution to undermine their old enemy, the British. In 1778, France and the United States signed a treaty and the French Army and Navy entered the war. French aid through supplies and military force would prove important to the successful founding of the United States. Among the supplies France sent to the Continental Army were many Model 1766 Cavalry Pistols just like this one. Brass was far more expensive than iron and was typically only used on weapons for the cavalry, navy, and officers. Brass is not only eye-catching, but it also the added benefit that it does not rust. This pistol was probably not used in the American Revolution but remained in storage. This explains why it is in such good condition and shows how it would have looked to soldiers at the time. -

Spanish 8 Reales "Piece of Eight"

Date: 1755

Origin: Lima, Peru and South America

Materials: Silver

Dimensions: 1 1/2” Diameter x 3/32” Deep

Gift of Susan and Larry Crabtree, Alabama Society

In the 18th century the Spanish “Piece of 8” was the most widespread type of money on the planet. People from China to Connecticut used it to buy goods and pay debts. When Spanish explorers learned of rich silver mines in the South American Incan Empire in the 1540s, they quickly took control of them. With this silver they minted coins worth 8 Reales, a Reale was like a Spanish dollar, and they came to be called the “Piece of 8”. These coins flooded the global economy and by the 18th century they were commonly found throughout the British colonies in North America. There was not enough British money in the colonies for people to conduct business, so the Spanish “Piece of 8” was prized by colonists. Early American dollars could be redeemed for Spanish silver coins which helped add value to the paper notes. This coin, made at the Spanish mint in Lima, Peru in 1755, could have been used in the British colonies to buy goods and would have been highly prized during the American Revolution when coins were scarce. -

American Flintlock Fowler

Date: Circa 1760s

Origin: American and European

Materials: Wood, Iron, Steel, Brass, and Silver

Dimensions: 66 3/4” Long x 9 1/2” High x 2 1/2” Wide; Barrrel: 50 7/8” Long

Gift of Neil S. Murray, Michigan Society

Conservation provided by a grant from the Artist Preservation Group

At the time of the American Revolution, people and armies depended on rivers and bodies of water for long-distance transportation. The Hudson River and Lake Champlain in the modern-day state of New York formed one of the most important “water roads” in the colonial era. In the fall of 1776 and again in the summer of 1777, the British Army tried to take control of this important waterway by invading south from Canada on Lake Champlain. Standing in their way was Fort Ticonderoga, controlled by the Continental Army. A militiaman named Beriah Murray travelled more than 70 miles from what is today New Hampshire to help defend Fort Ticonderoga. Beriah Murray obtained this fowler at the fort and carried it while he was in service. A fowler is a type of hunting firearm used in the 18th century to hunt birds and other small game. The Continental Army retreated from Fort Ticonderoga but later defeated the British Army at the Battle of Saratoga. Beriah Murray took this fowler home with him after the retreat and it remained in the Murray family until it was donated to the SAR. -

Lantern

Date: 1750-1800

Origin: Probably America

Materials: Iron, Glass, Brass, Tin

Dimensions: 20 1/4” High x 6 1/4” Wide x 6 1/4” Deep

Gift from LACASSAR in Memory of James Blauer

With the flip of a switch today, a room can be filled with light. In the 18th century however, having light after the sun went down was much more of a luxury This lantern, with a burning candle inside, was one of the best types of lighting available at the time. The lantern protected the candle from the wind and allowed it to burn brightly, giving off light that easily shown through the clear glass. Glass and candles were costly though and were used to give light for important work, traveling at night, and special events. There were other types of lighting available, but they did not give off as good of light as a lantern like this one. Without a source of light to work by after the sun set, many letters and documents of the American Revolution may have not been written. -

Miniature Portrait of Dr. James Craik Craik (1730-1814) by Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827)

Date: 1778

Origin: American

Materials: Brass, Ivory, Watercolor Paint

Dimensions: 1 1/4” High x 1” Wide x 1/2” Deep

Gift of Mary & James S. Craik

This miniature portrait was painted at the Valley Forge encampment between April 26 and May 7, 1778. It was painted with watercolors on a sliver of ivory. A jeweler then set the portrait in the brass frame that could be worn as a brooch or a pendant. Such portraits were typically given to a very close family member or friend as a keepsake while the person portrayed was away. Dr. James Craik was a close friend and personal physician to George Washington. Born and educated in Scotland, Dr. Craik moved to Virginia in 1751 and later met Washington while they served together in a Virginia Provincial Regiment of the British Army during the French and Indian War. During the American Revolution, Dr. Craik served in the medical department and continued to look after General Washington’s health during the war. The two men remained friends for life and Dr. Craik was an attending physician at Washington’s death in 1799. At the time of the American Revolution, Charles Willson Peale was a soldier in the Pennsylvania Militia and an aspiring artist. Peale painted miniature portraits of many leading military figures at Valley Forge. After the Revolutionary War he painted iconic portraits of prominent Americans, patented inventions, and opened one of the earliest museums in the United States. This miniature portrait remained in the Craik family until it was donated to the SAR.