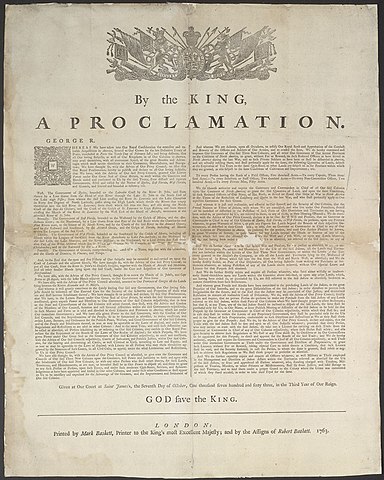

October 7, 1763 King George III issues The Royal Proclamation of 1763 to establish restrictions on expansion of the 13 North American colonies. Colonists were forbidden from settling west of an established proclamation line running north to south along the Appalachian Mountains. Citizens and colonial governments were not allowed to make agreements with tribal nations and only licensed traders could trade in the West. Settlers living in western territories were evicted. By reserving western lands for Indian use, the British addressed the violence between the Indians and settlers, sought to simplify colonial administration and reduce military costs. The Proclamation is considered the first British policy to set the colonies on a path to revolution.

250th Anniversary Timeline

-

The Proclamation of 1763

October 7, 1763

-

The Stamp Act

November 1, 1765The Stamp Act went into effect on November 1, 1765, and the American colonists refused to use the stamps, thus bringing almost all trade to a standstill. Just weeks earlier, the Stamp Act Congress met in New York with delegates from Connecticut, Delaware, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and South Carolina. It was at this historic meeting that the phrase “taxation without representation” was first used in an official document that was forwarded to King George III and the English Parliament. The delegates to this convention returned to their colonies and, in a show of non-violent unity, had their leading citizens sign resolutions which forbade the purchase of English trade goods until the Stamp Act was repealed.

-

Townshend Acts

1767

These acts imposed taxes on imported British goods such as paint, lead, china and tea. The British chose these goods because they felt they would be difficult for American’s to produce on their own. These acts deeply angered the colonists, especially since they lacked representation in Parliament. Famous pamphlets, such as “Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania” by John Dickinson began circulating around the colonies in response, and the colonists began boycotting British goods. While most of the Townshend Acts were repealed in 1770, lines had already been drawn and tensions between the British and the colonies would only continue to worsen in the years ahead.

-

The Battle of Alamance

May 16, 1771May 16, 1771, the Battle of Alamance begins in Alamance County between North Carolina farmers calling themselves Regulators and the Royal Governor William Tyron’s colonial militia. The Regulator Movement’s earlier attempts to protest taxation, expensive land, and government corruption through the formation of associations and written petitions failed to achieve a response from the royal government, and tensions came to a head. While Regulators outnumbered the militia, the militia brought a battle plan to the field under trained officers and well-armed soldiers, resulting in the Regulator’s defeat. Governor Tyron offered to pardon Regulators who swore allegiance to the Crown, yet many continued the fight for freedom.

-

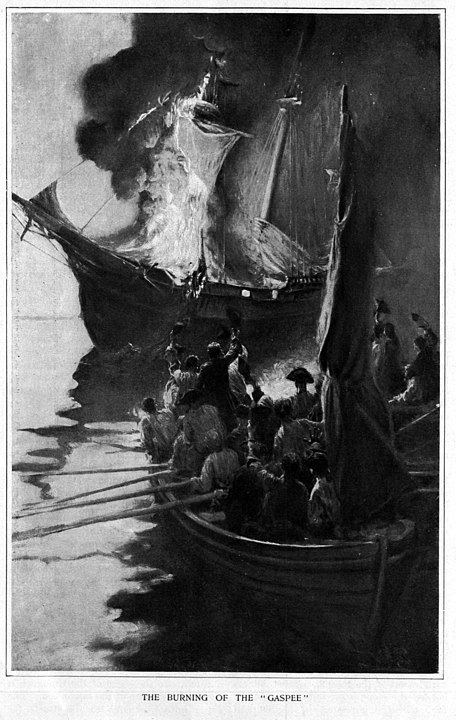

The Gaspee Affair

June 9, 1772

When the British HMS Gaspee entered Narragansett Bay in Rhode Island, the stage was set for an act of defiance by American colonists against Great Britain. Gaspee’s orders were to enforce British maritime trade regulations that residents avoided by smuggling goods.

Frustrated residents responded to British enforcement by luring the Gaspee aground and proceeded to capture the crew and burn the schooner. King George III and Parliament were furious at this attack on their colonial powers. Great Britain established a Commission of Inquiry and offered a reward for information on attackers.

The government gave the commission authority to send suspects directly to England for trial. Colonists thought this action violated the American court system and threatened colonial rights as Englishmen established by Anglo-Saxon law and the Magna Carta. The colonies reacted by creating the Committees of Correspondence and began planning the First Continental Congress.

The Gaspee Incident planted the seed of independence in the colonies. Newspaper accounts of the Gaspee and the Commission of Inquiry appeared in the colonies and Great Britain. A popular pamphlet, The Essential Rights of the Americans written by Rev. John Allen highlighted the Gaspee incident and protested British tyranny. Often quoted by John Adams and James Otis the pamphlet warned the injustices may cause armed rebellion.

-

Virginia Establishes a Committee of Correspondence

March 12, 1773

Finding Great Britain’s intentions to send Gaspee Affair suspects to England for trial unconstitutional, the Virginia House of Burgesses responded by establishing an intercolonial committee of correspondence. The committee provided a communication network among colonial legislatures to create a unified approach to intrusions on the rights and liberties of American colonists.

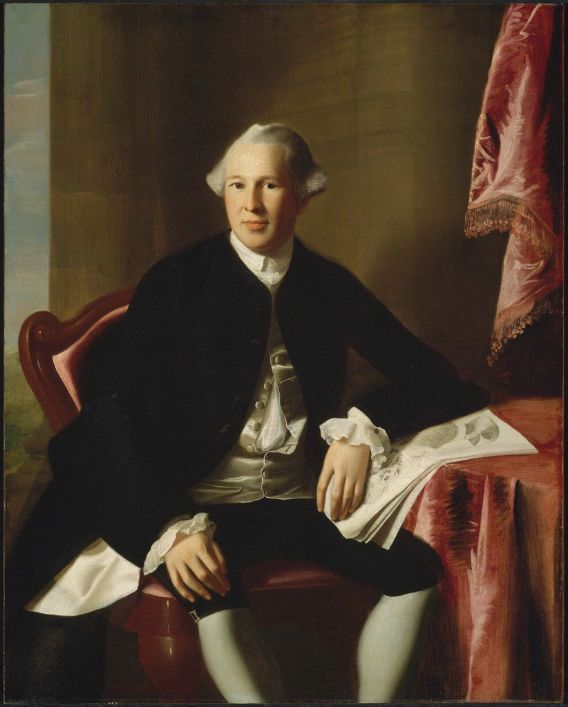

Peyton Randolph a respected Virginia leader of the House of Burgesses, served as the leader of Virginia’s intercolonial committee of correspondence. It consisted of eleven members and included Thomas Jefferson, Richard Henry Lee, and Patrick Henry. The House of Burgesses directed the committee to obtain early and accurate details of Parliament Acts and resolutions, educate and unite citizens in defense of their constitutional rights as British subjects, and to report back.

The committee’s existence under the authority of Great Britain’s representative body made organized resistance challenging and cautious of radical ideas. While they achieved limited success it began to communicate colonists’ concerns and contributed to the formation of the First Continental Congress. By 1774 inter-colonial committees of correspondence existed in all thirteen colonies except Pennsylvania.

-

The Boston Tea Party

December 16, 1773

Early in 1773 America and Great Britain foresaw few issues with tea shipments. Circumstances changed when seven ships sailed from Great Britain to America carrying East India Company tea regulated by the Tea Act. It allowed the East India Company to sell tea directly to colonists. Officials ordered the ship’s owner to pay a duty within 20 days of entering the port or risk the cargo’s seizure.

Three ships, the Eleanor, Beaver, and the Dartmouth loaded with tea entered Boston Harbor and sparked a meeting of Bostonians at Old South Church. Parliament claimed the Tea Act was not about taxation, but Americans felt threatened and voted not to unload the tea. Bostonians urged officials to ship the tea back to England without paying the duty. Yet others supported British authority and Governor Thomas Hutchinson ruled the meeting illegal.

Faced with the tea’s seizure, men called “Mohawks” boarded the ships at Griffin’s Wharf. The men broke open 342 tea chests filled with forty-six tons of tea worth over $1.7 million and tossed it into the water. Destroying the tea cargo was one of Boston’s most destructive events. In America and Great Britain discussions took place about compensating the EIC for their losses. Yet the Massachusetts Assembly blamed the unwillingness of others to compromise and resorting to violence.

-

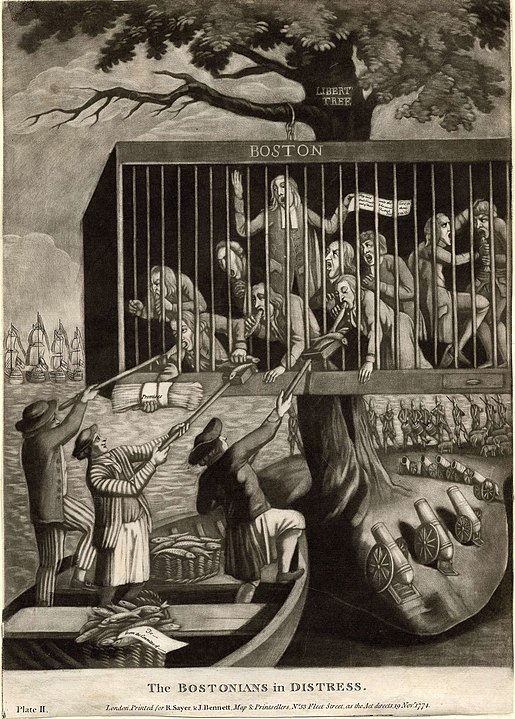

The Intolerable Acts

March-June 1774

Great Britain passed four Coercive Acts to punish the Massachusetts Bay Colony for the Boston Tea Party. The four acts: Boston Port Act, Massachusetts Government Act, Administration of Justice Act, and Quartering Act. Along with the Quebec Act, that established new territorial administration, Americans found them cruel and called them the Intolerable Acts.

The Boston Port Bill closed Boston’s port until the cost of the destroyed tea was repaid and demonstrated the power of Great Britain’s Navy. The port’s closure crippled Boston’s economy. With business at a standstill, Great Britain passed the Massachusetts Government Act that placed the royal colony under its direct control and eliminated its chartered ability to self-govern.

Great Britain was skeptical of the American justice system and responded by passing the Administration of Justice Act. Under the act British soldiers were sent to England for trial and viewed by many colonists as a way for them to avoid justice.

The Quartering Act applied to all the colonies. British soldiers would be housed or “quartered” in homes and buildings secured by royal governors instead of colonial legislatures. Colonists were enraged by Great Britain’s action to house foreign soldiers in their communities.

Great Britain used The Intolerable Acts to reinforce British authority and remind colonists that they were governed by Parliament and the Crown.

-

British Occupy Boston

March 18, 1774

When news of the Boston Tea Party reached Great Britain, King George III determined that the colonists had disrespected the Constitution and were impacting British commerce.

Responsibility fell to Prime Minister Lord North to craft legislation that reprimanded the Massachusetts Bay Colony for their rebellious actions. On March 18, Lord North presented the Boston Port Bill to Parliament. The Act closed Boston’s port until the East India Company received reimbursement for their loss, and order was restored. Under the Boston Port Act, colonial exports to foreign ports ceased and American imports were limited to British Army provisions and basic goods such as fuel and wheat.

By cutting off Boston merchants from trade, Lord North aimed to achieve peace in the colony but instead created outrage against Parliament and the Crown. The Boston Committee of Correspondence responded by calling for a boycott of British goods and sought support for the trade embargo from Salem and Marblehead ports. Bostonians held mixed opinions of the city’s punishment. Outside of New England, colonies called for consideration of alternatives to nonimportation and nonexportation of British goods. Alternatives included reimbursing the East India Company and calling for an intercolonial congress. Conflict arose throughout the colonies between the desire for order and the fear that what happened in Boston could occur in other ports.

-

The Powder Alarm

September 1, 1774

Decades of French and Native American attacks compelled colonists to stockpile munitions for protection. After the Intolerable Acts and the Boston Tea Party, Great Britain identified the traditional gunpowder stores as a threat to maintaining peace. Great Britain sent General Thomas Gage to America and appointed him Royal Governor of Massachusetts to restore order.

Militia leader and loyalist William Brattle notified General Gage about an increase in local militia and that colony-owned gunpowder was stored northwest of Boston at the Charlestown Powder House. General Gage ordered 300 troops to secretly sail to Charlestown, seize the colony’s remaining legal gunpowder and secure it at Castle William. British troops were unprepared for the colonists’ reactions that viewed the troops as a sign that war was approaching with Great Britain. British secrecy led to false rumors: that the colonies were “up in arms,” British ships and troops were firing on Boston, and six people were dead.

Four thousand colonists gathered on Cambridge Common for revenge and to protest the exhibit of royal power. When Brattle’s role became public the colonists’ fear turned to rage. Protesting colonists surrounded Lieutenant Governor Thomas Oliver’s home demanding his resignation and received it. Inspired, American colonists drew closer to a revolution.

-

First Continental Congress Convened

September 5, 1774

To unify the colonies’ response to the Coercive Acts the First Continental Congress convened on September 5, 1774, at Carpenters’ Hall in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Seven weeks of secret debate among delegates produced the colonies’ economic response to the Acts referred to in America as the Intolerable Acts. Representing 12 of the 13 colonies (Georgia declined) the 56 delegates were selected by colonial assemblies, and the Committees of Correspondence. Delegates included prominent colonists and leaders of the future United States: George Washington, John Adams, Roger Sherman, Peyton Randolph, Patrick Henry, Samuel Adams.

Within eight days of convening, Congress accepted The Suffolk Resolves encouraging Massachusetts to boycott British goods within the colonies in an orderly manner. It called for an end to exports to Great Britain if the Acts weren’t repealed by September 10, 1775.

Delegates proceeded to address a second document, the Declaration and Resolves of the First Continental Congress listing the rights of colonists, objections to the Intolerable Acts, and itemized objections that went beyond the Acts. This Declaration asserted colonists’ rights to participate in their government without designating limits on Parliament’s trade regulations.

On its last day in session, Congress approved a formal petition to King George III outlining the colonies’ grievances against Parliament. At the same time, the Massachusetts Provincial Congress reorganized its militia and designated them Minutemen.

Congress agreed to reconvene in Philadelphia on May 10, 1775, not expecting war to break out. Their decision to reconvene created an unprecedented intercolonial decision-making body.

-

The Suffolk Resolves

September 9, 1774

Angered by Parliament’s Coercive Acts, Suffolk County, Massachusetts held a county convention where an appointed committee presented 19 resolves focused on a probable independent future. The Suffolk Resolves urged Massachusetts to establish a separate free state until Parliament repealed the Coercive Acts and to appoint militia officers and begin arming local forces. Finding the Coercive Acts unconstitutional and void, Suffolk Resolves demanded the resignation of officials charged with their enforcement. It warned General Thomas Gage not to arrest citizens on political charges.

The Suffolk Resolves used bold language, italicized key words, and established goals that exceeded other colonies’ protests, earning Massachusetts a leadership role in the resistance against British policies. While declaring loyalty to King George III it stated, “an indispensable Duty” to defend established “civil and religious Rights and Liberties.” Yet colonists no longer felt they owed loyalty to a king who violated these rights. Sensitive to maintaining social order, the Suffolk Resolves instructed colonists to conduct themselves in an orderly manner while opposing British measures.

Respecting Continental Congress recommendations, the Suffolk Resolves recommended a publicly funded system for defense. It advised tax collectors to halt payments to the Massachusetts treasury until the government “was placed on a constitutional Foundation.”

Proposed by Dr. Joseph Warren on September 9, 1774, they underwent revisions and then were unanimously accepted. Paul Revere delivered the Suffolk Resolves to the First Continental Congress meeting in Philadelphia where on September 17, 1774, Congress endorsed them.

-

Battles of Lexington and Concord

April 19, 1775

April 19, 1775 was when shots rang out in the first battle of the American Revolution, the Battles of Lexington and Concord. Conflicts had been simmering for years between the American colonists and the British, with the Americans incensed by the increasing British restrictions and taxation. After learning that the Americans were amassing an arms stockpile, Massachusetts Royal Governor Thomas Gage ordered British troops to Concord to capture the weapons. Paul Revere and other midnight riders warned local militias who mustered in time to meet British troops at Lexington on the morning of April 19th. After brief fighting, the British then moved on to Concord where a greater number of minutemen were ready and the British opened fire. The Americans responded in turn with the “shot heard ‘round the world”. The British were outnumbered and retreated to Boston facing attacks along the way. This decisive American victory set the stage for the War for Independence.

-

Capture of Ft. Ticonderoga

May 10, 1775

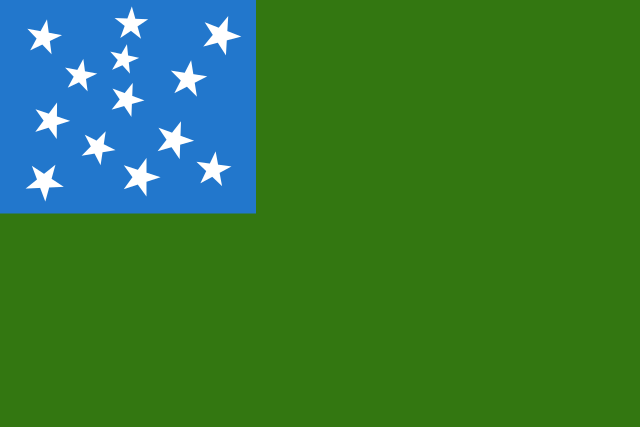

On May 10, 1775 Colonel Ethan Allen and his Green Mountain Boys from New Hampshire captured Fort Ticonderoga in upstate New York. Although some history books give credit to Benedict Arnold for this capture, he had only a small band of men with him, while Allen, under orders from Connecticut, had two to three hundred Green Mountain Boys. In a report by Lieutenant Jocelyn Feltham, an officer at the fort, we learn the following: “Mister Allen held a drawn sword over my head while his men aimed their flintlocks at me. He insisted I give up the fort or else they would kill every man, woman, and child if I did not comply. Meanwhile, Mr. Arnold begged in a genteel manner, but without success, for us to surrender the fort.

-

Battle of Bunker Hill

June 17, 1775

After the Battles at Lexington and Concord, the Americans learned of British plans to surround the city of Boston with troops. This led the colonists to fortify Breed’s Hill (where most of the battle took place) and Bunker Hill. When the British attacked, General William Prescott was said to have uttered to “not fire until you see the whites of their eyes.” The Americans were able to hold off the British forcing them to retreat twice. Eventually ammunition began to run low and the colonists were forced into hand-to-hand combat. While the British won the battle, they suffered greater casualties than the Americans despite having more troops. The significant British casualties boosted the colonists’ self-confidence in their fighting abilities.

-

Battle of Trenton

December 26, 1776

After months of defeat and retreat, General Washington knew he needed a victory and his best chance would be against the Hessian garrison in Trenton. Washington’s plan was to split his army in half: while he crossed the Delaware north of Trenton, General Ewing would cross to the south. But due to icy conditions, Ewing could not move his men and artillery across the Delaware and was forced to abandon this plan. So, on the morning of December 26, 1776, during a violent storm, only half of the American army staged their attack and caught the Hessians by surprise. The patriot cause which had seemed helpless took on a new life and much hope.

-

Battle of Bennington

August 16, 1777

Local Tories told General Burgoyne that the rebels had built up an important military supply base in Bennington and was guarded by only a few hundred men. As Colonel Baum and his eight hundred men were marching toward the supply base, Brigadier General John Stark was on his way with reinforcements. On August 16, the battle began, with the patriots holding a two-to-one advantage. Around three o’clock, Stark mounted his horse and called to his men, “There they are! We’ll beat them, or Molly Stark is a widow tonight!” Heavy fighting continued for several hours and did not cease until Colonel Baum was killed.

-

Battle of Brandywine

September 11, 1777

The Battle of Brandywine took place along the border of Delaware and Pennsylvania. While Washington’s army was camped in Wilmington, a port city of the Brandywine River, General Howe landed at Head of Elk at the mouth of the Delaware River, about twenty miles south of the American camp. Washington made his stand at several fords along the Brandywine, but left open Trimble’s Ford to his north. When Howe found the American defenses, he ordered General Knyphausen and his Hessians to stage a mock frontal attack while he and Cornwallis crossed in the north and attacked Washington’s left flank and rear guard. Howe once again outsmarted and outflanked Washington.

-

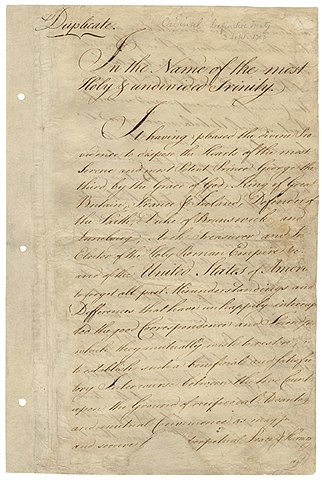

The Treaty of Alliance

February 6, 1778

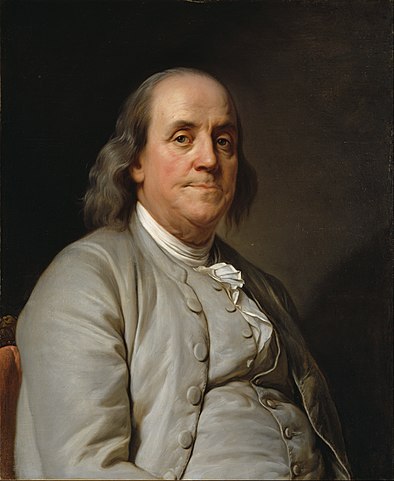

The Treaty of Alliance was signed between the United States and France. It was negotiated by Benjamin Franklin, Silas Deane and Arthur Lee, and was the first treaty of the new American government. This military treaty promoted stronger trade and commercial ties, while stating that neither France nor America would sign a separate treaty with Great Britain, and that American independence would be a necessity on any future accord. France was eager to assist the American colonists’ battle against Great Britain, as it had hoped to regain some of its North American territories. The French government had been quietly sending aid to America prior to this coalition, but the Treaty of Alliance made France’s full support official.

-

Battle of Lake Pontchartrain

September 10, 1779The battle of Lake Pontchartrain took place near New Orleans on September 10, 1779. At this time, the Spanish governor of Louisiana and local merchants were secretly funding the American rebel cause to quietly move goods along the Mississippi River, while British ships patrolled the British-held province of West Florida which bordered the lake. One such ship outfitted to protect trading vessels was the schooner Morris, captained by American William Pickles. Pickles and his crew were falsely posing as a British ship when they confronted a real British sloop-of-war, the HMS West Florida, commanded by Lieutenant John Payne. The Morris’ crew quickly changed their flag and boarded the enemy ship, subduing the crew, mortally wounding Payne in the process, and claiming the craft for the American campaign.

-

Battle of St. Louis

May 26, 1780In 1780 St. Louis was a French settlement in Spanish Louisiana. Spain had entered the Revolutionary War in 1779. Hoping to gain control of the Mississippi River, the British and their Native American allies targeted St. Louis, the governing center of northern Louisiana. The local militia in St. Louis, led by Fernando de Leyba, Lieutenant Governor of Spanish Louisiana, had received word earlier in the year from traders about a coming attack by the British, allowing them time to secure the city by building a tower, trenches, and strategically placing cannons. While many settlers were captured or killed, the local forces were able to hold off the British, making it the last British attempt to control the Mississippi River during the war.

-

Surrender of Cornwallis' Army at Yorktown

October 19, 1781

This final British disaster may be attributed to several causes: Cornwallis’ unwise encampment, his triangular division of troops, frightened British naval commanders, but most of all, Washington’s flexible strategy. The siege of Yorktown began in the afternoon of October 10 and continued until the English surrendered nine days later. The official ceremony was to take place on October 19, 1781, though General Cornwallis refused to attend. This ended the last major engagement of the American Revolution.

-

Battle of Eutaw Springs

September 8, 1781

The last major southern battle of the Revolutionary War occurred at Eutaw Springs in South Carolina. General Greene placed the North Carolina militia in the center of his front lines, with South Carolina militia on either side, and posted cavalry on both flanks. His plan was working smoothly until the Virginia and Maryland Continentals broke ranks as they overran the British campsite. Naked, starved, and thirsty, they stopped to taste the spoils of war. This gave the English major, Major Marjoribanks, the opportunity to reassemble his fleeing army and then push the American Regulars into the woods. Three hours of bloody battle and intense heat was enough for both sides, so they disengaged. Major Marjoribanks did: he died, as did twenty percent of his men.

-

Last Naval Battle of the Revolution

March 10, 1783March 10, 1783, marks the final naval battle of the Revolutionary War. On March 10, Commodore John Barry and his ship the Alliance, along with a French ship called Duc de Lauzun, were filled with Spanish bullion which was destined for Congress to establish our first national bank. As they were sailing along the coastline of Cape Canaveral, Florida, they spied a couple of English frigates and decided to outrun them, but the Duc de Lauzun was too slow, so Barry stood and fought. With a fifty-gun French warship nearby, only one, the Sybil, decided to engage the Alliance. After a short sea battle, the Sybil’s guns were silenced. Thus the last naval battle of the revolution goes to Florida, even before it became a state.

-

Treaty of Paris

September 3, 1783

This treaty between the United States and Great Britain was the official end of the Revolutionary War. It established the independence of America as a nation and outlined U.S. borders. The United States gained land westward to the Mississippi River while Canada remained in British hands. All debts owed to creditors in both countries were still to be collected and British Loyalists in the United States were offered protections and the return of their confiscated property. Three men represented the United States in the negotiations: John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, and John Jay, while Richard Oswald represented Great Britain. The Continental Congress ratified the treaty on January 14, 1784.

For more information and resources on America250 SAR click here.